Kevin Berris Ann Arbor Play It Again Sports

The 24-hour interval that Kevin Harrington went into quarantine was a joyous ane.

He flung open the door to room No. 305 at the Extended Stay America in Canton, Mich., and flopped downwards on the full-sized mattress, which felt so costly he imagined he was on a cloud.

The side by side day he took three long, hot showers — but because he could.

He ordered in hamburgers, fries, milkshakes, thick slabs of French toast crusted with cornflakes and topped with bananas Foster sauce, candied pecans and mixed berries.

More once he simply told the person taking his order: "Surprise me."

For many Americans, quarantine in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic has been a sort of prison. For Harrington, it was freedom.

Kevin Harrington loads his belongings into his nephew'south car, putting an terminate to his quarantine.

(Family photograph)

He knew what existent prison was similar, having come directly from the Macomb Correctional Facility, where he had been serving a life sentence for murder until a judge exonerated him.

Now, afterward most 18 years, he was no longer inmate No. 447846.

::

Growing up outside Detroit in the predominantly black city of Inkster, Harrington never thought much about freedom, even when he saw police arresting drivers or harassing neighborhood kids.

He was the youngest of three children, all raised by their female parent, who worked equally a nurse's aide for psychiatric patients in residential treatment centers. They would encounter their father on weekends.

Harrington did well in school, and in the fall of 2002, the twenty-year-former became a freshman business major at Wilberforce University in Ohio — the first in his family unit to attend college.

"There was a bully hereafter awaiting him," said his mother, Pauline Lawrence. "I was so proud."

Then on Oct. 19, 2002, Harrington was at a bus station in Ann Arbor when six police officers walked upward to him and said he was nether arrest for murder.

A witness had implicated him in the homicide of a 45-year-sometime man whose body had been left in a field in Inkster three weeks earlier. In a long interrogation, the witness told police that she had seen Harrington and another man beat the victim with a pipe before shooting him.

Harrington's outset prosecution ended in a mistrial. As prosecutors prepared to retry him, he vowed to establish his innocence.

In the meantime, he began to larn how to survive behind bars.

'Liberty to me means doing the right affair, real justice.'

— Kevin Harrington

Each morning before his anxiety touched the concrete floor in his cell at the Wayne Canton jail, he told himself: "Today is the day that victory is hither." Then he would pray and put on earphones to listen to the same gospel music his mother blasted in the business firm.

Whenever he would make a collect telephone call, the person on the receiving finish would hear: "You lot accept a collect call from Blest and Highly Favored."

In the spring of 2005, Harrington went on trial over again.

The case appeared to fall apart when the woman who claimed she had seen the killing took the stand and recanted the statement she had given to law. Just the trial ended in a hung jury, equally did a tertiary trial that fall.

Prosecutors then offered Harrington a bargain: Plead guilty and get dwelling house in four years. It was a sure path to freedom.

But he refused.

"I wanted nothing more than to go home, simply I was willing to cede my life for what's right," he said. "Freedom to me ways doing the right matter, real justice."

And and so in Jan 2006, Harrington went on trial for the 4th time.

The cardinal witness again testified that she had fabricated upwardly her original argument, but the judge allowed it to be read in court anyway.

The jury deliberated for 2 days before finding Harrington guilty. He was sentenced to life in prison house with no possibility of parole.

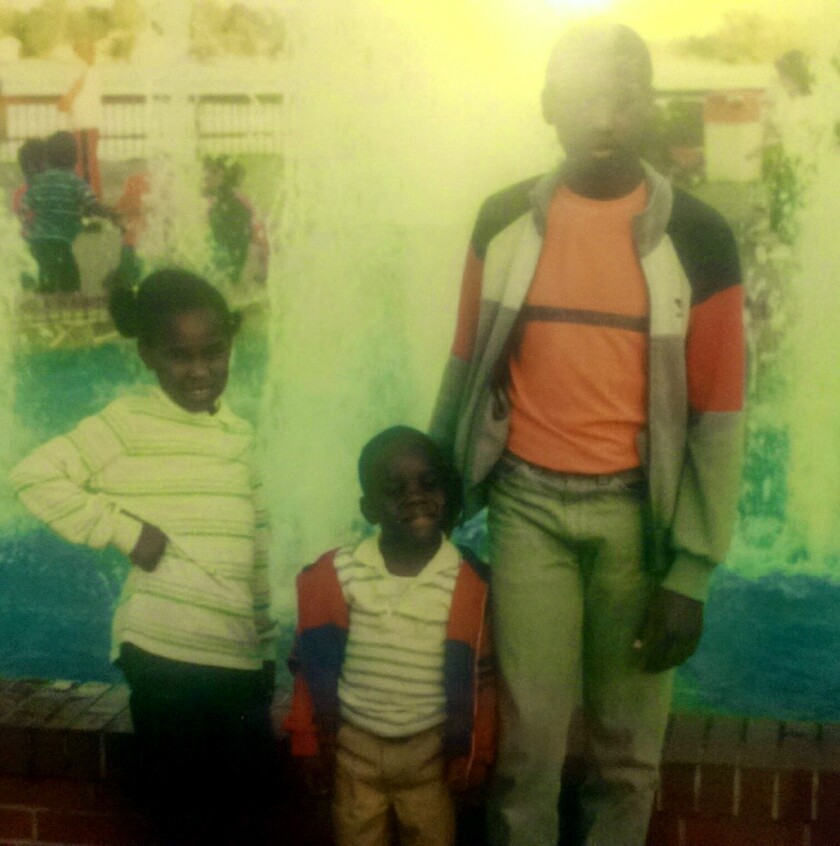

Kevin Harrington, centre, with sis Sherica and brother Michael.

(Family photo)

::

Harrington was transferred from the county jail into the state prison system. Over the next 14 years, he lived in thirteen different lockups.

The toughest period was his 3 years at the Chippewa Correctional Facility upstate, because his female parent and nephews could only make the drive — 335 miles each manner — every 4 or five months.

He called each of them collect every other day and tried to make sure they all knew they could talk most annihilation — "big stuff, little stuff, breakups, whatever."

But each telephone call was automatically cut off after 15 minutes.

Equally years passed and Harrington established a tape of model behavior, he was allowed to spend more fourth dimension outside his cell. He relished the opportunity to lift weights and attend a Protestant service each Sunday.

Merely his nigh cherished retreat was the police force library. Each prison house had one, and Harrington spent equally much time as he could researching his instance, which in 2009 was taken upward by the Innocence Clinic at the Academy of Michigan Law School.

In his listen, learning was the closest affair to liberty. He never minded helping other inmates with their legal proceedings.

One 24-hour interval Harrington was returning to his jail cell when a friend — known to everyone equally Large Pee-wee — saw him sobbing. A judge had only turned downwardly all the same another one of his appeals.

Big Pee-wee hugged him and said, "Listen, human being, you lot gonna make it outta here. Believe that."

But leaving one prison only meant relocating to another.

When he arrived at Macomb in 2017, he was disappointed to detect that his cell — which he shared with some other inmate — was only ten feet long and 7 ½ feet wide.

Information technology had a bunk bed, two desks and two lockers, but no toilet. If he needed to go subsequently lights were out, he had to concur it. If he got thirsty during the nighttime, tough.

Only at least information technology was only 40 minutes from Inkster, so his family was able to visit near one time a month.

Harrington also establish his mode back to a higher classroom. He was one of ten inmates who attended a University of Michigan philosophy class alongside 10 undergraduates who visited the prison each Tuesday evening for an entire semester.

He besides would have liked to study cooking, horticulture or auto shop, but those classes were not open to lifers.

::

It would take the work of 27 unlike constabulary students over the course of a decade, just the case for Harrington's exoneration began to take shape.

Records showed that the fundamental witness had denied any knowledge of the offense at least 23 times before the detective interrogating her repeatedly suggested that she could exist separated from her children if she failed to supply the information he wanted.

Last autumn, the Wayne Canton Prosecutor's Conviction Integrity Unit, which investigates claims of innocence, took upwards the case, and by this spring, Harrington and his legal squad began to feel hopeful.

But first he had to survive the pandemic.

Prisons beyond the country were existence ravaged by the virus, and Michigan was no exception. At to the lowest degree 62 inmates beyond the state would dice of COVID-19.

Many of the freedoms Harrington had enjoyed disappeared as prison officials tried to slow the spread. In late March, they canceled religious services and closed the law library.

Classrooms were converted into isolation wards for the infected. With the mess hall airtight, Harrington and the other inmates ate in their cells.

"I ain't virtually to let no lilliputian coronavirus scare me," Harrington said he thought at first. "... I'd already been fighting for my life for 17 years, then I figured, 'Alright, gauge I gotta fight yous too.' "

Then the virus killed William Garrison, one of the inmates who would sometimes join him to written report law and, afterward most 44 years in prison, was slated to be released in May.

Kevin Harrington packs upwardly to leave a hotel in Canton, Mich.

(Family unit photograph)

"He was on his way domicile," Harrington said. "It's sad. Very, very pitiful."

On April 21, 8 days after Garrison's decease, the approximate threw out the murder convictions of both Harrington and the other man who had been falsely defendant by the aforementioned witness and wrongly bedevilled.

::

Harrington found out an hr later, when a guard asked for his clothing size in gild to supply him with khaki get out garb.

He thanked the officeholder but turned him downwards before rushing to the phone banks to identify his last collect call from prison house.

"We're on our way!" his female parent screamed.

Harrington returned to his cell, put on his own white T-shirt and maroon shorts and grabbed his 13-inch flat-screen television receiver, earphones, packs of ramen noodles and other possessions. Then he walked down the corridor handing them out through the confined.

As for the things he wanted to keep, he filled one giant trash pocketbook with letters and photos and four others with his legal paperwork, and then piled them all onto a pushcart.

At 3 p.thou., he exited the administration building's sliding doors, stepped into the parking lot, fell to his knees and thanked God. He was 37 and a costless man.

His mother shrieked and banged a tambourine against her palm as she resisted the urge to encompass her son. Their faces covered past masks, relatives and friends cheered from a safe altitude.

And then ane of his nephews, who is a nurse, collection him to the hotel and helped him sanitize the room.

Cavalcade One

A showcase for compelling storytelling

from the Los Angeles Times.

Harrington didn't have any symptoms of the coronavirus. Only he thought it best to spend 14 days in solitude.

"I understand the significance of doing the right thing in regards to social distancing," he said. "I have older people in my family and definitely don't want anything to impact their well-being."

Relatives had chipped in to buy him an iPhone, and he spent that kickoff evening of freedom FaceTiming with them.

Around viii p.m., he decided to take a walk simply was unable to bring himself to leave the hotel parking lot. Prisoners were never allowed out at night.

He felt exhausted simply struggled to fall comatose in the darkness. Finally, he turned on the bathroom lite, remembering that in prison he'd gone to bed with the lights on.

The side by side morning, he prayed, but as he had when he was locked up. After breakfast, he took another walk, this time going a few blocks. Information technology became his morn routine.

Each twenty-four hour period Harrington ventured farther. He wore a gray pleather mask, simply somewhen he started taking information technology off. He liked the feeling of the air on his mouth.

Back in his room, he would flip on the television and sentry the news for hours. He strongly disagreed with protesters who claimed stay-calm orders were a violation of their freedoms.

Soon he found "The Last Dance," the ESPN documentary serial about Michael Hashemite kingdom of jordan, one of his babyhood heroes.

Harrington marveled at all the things now under his command. When to eat. When the lights go along and off. When to creepo up the thermostat. How long to stay on the phone.

That was freedom.

Two constabulary students who had worked on his case set a GoFundMe page that has raised more than $22,000 to help him restart his life. He planned to rent an apartment as before long every bit quarantine ended.

A selfie of Kevin Harrington at Walmart.

(Kevin Harrington)

Under Michigan's Wrongful Imprisonment Compensation Human activity, he may be entitled to nearly $900,000. His attorneys also program to sue the metropolis of Inkster and the detective who handled the example. Money could start to correct the injustice.

But what Harrington said he believes would really be fair is that those who worked to incarcerate him spend 17 years, six months, two days and 35 minutes away from their loved ones — all that time wondering, How the hell am I even here?

Back in his hotel room, he could practice as he pleased — even take a break from his quarantine.

After 4 days, he was running out of shampoo and make clean socks and realized he also desperately needed new lenses for his glasses. He had to make it through the side by side 10 days lonely.

His nephew picked him up and drove him to Walmart.

There was an unabridged alley just for shampoo. He didn't know where to start. The optical department, he was told, was closed because of the pandemic.

"When volition it reopen?" he asked a saleswoman.

"Who knows?" she said.

Harrington could expect. He had time.

Source: https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2020-05-29/michigan-man-exonerated-then-went-into-quarantine-coronavirus

0 Response to "Kevin Berris Ann Arbor Play It Again Sports"

Post a Comment